Brooklyn Rail

In Conversation

Don Voisine with Ben La Rocco and Craig Olson

by Ben La Rocco and Craig Olson

Brooklyn Rail

June 2009

A week after the opening of his exhibit of a new group of paintings, which will be on view at McKenzie Fine Art Inc, located at 511 West 25th Street, till June 6, 2009, the painter Don Voisine visited the Rail’s Headquarters to talk with Assistant Art Editor Ben La Rocco, and contributing writer Craig Olson about his life and work.

Portrait of the artist. Pencil on paper by Phong Bui.

Ben La Rocco: Lets talk about your early life in Maine.

Don Voisine: I was born in Fort Kent, Maine in 1952. Fort Kent is a northern border town on the western-most edge of New Brunswick just 10 miles from the Quebec border. The majority of townspeople are of Acadian descent and speak French, the principal industry is potato farming and lumbering. My father died when I was three and my mother never remarried. She worked two jobs to support and raise three kids. From the time we were ten we also worked part time and after school.

La Rocco: Are there any particular influences you remember from that time?

Voisine: While a senior in high school I played drums in a garage band called Mantra, hence my lifelong interest in music.

La Rocco: Do you really think Ike Turner is the greatest electric blues guitar player of all time?

Voisine: He was a phenomenal musician. At nineteen he was an A&R man for Sam Phillips and he brought people like B.B. King and Howlin’ Wolf to the studio for the first time.

Craig Olson: Right.

Voisine: And he played piano on some of those tracks. Then he started playing guitar. He had a great band in the mid-50s: The Kings of Rhythm. They recorded some terrific tracks on Federal Records out of Cincinnati. He’s the one who plays guitar on some of those incredible Otis Rush Cobra singles.

Olson: Yeah, they’re so great.

Voisine: But I’m just not into virtuosity in guitar playing for it’s own sake. That’s like a white boy thing. It’s frantic.

Olson: Unless you’re Albert King.

Voisine: I went to see Buddy Guy in Central Park and it got totally boring because he was playing to the crowd, just going on and on with these extended guitar solos. I’d love to see him in a small club on the South Side of Chicago. That would be more the kind of music I’m interested in.

Olson: Yea, I hear you. I used to go down to Muddy Waters’s old club on the South Side, the Checkerboard Lounge, and there was this guy, Vance “Guitar†Kelly. And he could play, he could play all those licks, but he didn’t show off. But when he would play that way, as in this song called “Candy Lickerâ€â€”you know that song? “I got me a candy licker, lick my candy all night long.†And he would make frat boys from the audience come up on stage and act it out. It was the most humiliating thing in the world. It was so funny. [Laughter.]

La Rocco: Don, what was your education like?

Voisine: I attended what was then the Portland School of Art; it’s now the Maine College of Art. I received an honorary BFA from the Maine College in 2000. The Portland School of Art, or PSA, was one of the last regional art schools in the country. Half the faculty did watercolors of the Maine seashore. We had lots of figure drawing classes and made many field trips to do plein air watercolors of nature. After 2 1/2 years of this, in 1973, I transferred to an alternative art school in Portland called Concept Center for Visual Studies. Concept was a short-lived program that broke away from the PSA. It was started by William Manning who, back in the 60s, was one of the few abstract painters in Maine, and a few others who disagreed with the PSA’s teaching philosophy. The faculty at Concept seemed more attuned to what was going on in New York and encouraged us to experiment. They did not have structured classes. You saw the faculty when you wanted to or had something to show them. As students we learned as much from each other as we did from the teachers. I met Kathy Bradford there. We, along with Maury Colton, had many intense and passionate discussions about art. This was my unofficial graduate school. Concept was located above a cosmetology school on Congress Street. The smell of hair products filled the corridors and mingled with the smell of paints. This has left me with an indelibly visceral memory of the place. I think one of the best ways to learn about art is to look and see what other artists have done. Learn how to look hard, seriously, and in an engaged critical manner, then use the same standards when considering your own work.

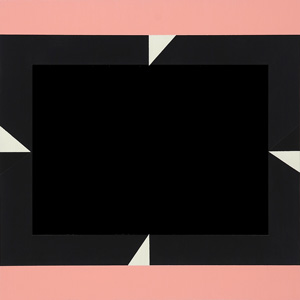

Don Voisine, “Wheel†(2008). Oil on wood. 25 × 20 inches. Courtesy McKenzie Fine Art, New York.

La Rocco: Is there a metaphorical intent to your paintings? Do the dark areas represent an absence or a void?

Voisine: Well, I do think of it as an absence, but it’s also full. It has weight, you know, a presence. It can be read both ways, a void, or something weightier.

Olson: And that’s important for you, that it’s read that way.

Voisine: Yes. In my work I like to get different readings. The white ground can be read as a negative or a positive, and it can vary from painting to painting, but generally I try to have things operate on a number of levels.

Olson: Yeah. So maybe even spatially, then, those areas flip back and forth.

Voisine: To me, that’s the air that activates the space of the paintings. That’s where the paintings breathe.

La Rocco: Despite all the black in the paintings, they never seem moody or maudlin, which is in contrast to a lot of other painters who use dark colors.

Voisine: Well, I’ve done some of those paintings, but I’ve also worked really hard to eliminate any sense of mourning from my work. I think a lot of art in the twentieth century, modernist work, has a sense of mourning to it.

La Rocco: How do you see your work in relationship to the Modernist tradition? I think of a lot of modernist work as having to do with negation or an abject condition.

Olson: I think they were also trying to neutralize space, and I don’t think you’re necessarily trying to do that, Don.

Voisine: I’m not trying to make a break from the past. I think I work in dialogue with it. But I’m also trying to make something that is relevant now, a different way of thinking about abstraction. One of those things is space. Like, Greenberg’s formalism is about flatness. I’ve always been trying to bring a kind of visual space into my work. Not something illusionistic, but a real visual space.

Olson: Would you consider that analogous to the way you experience space in your life? Where does it come from?

Voisine: I’ve made my living painting apartments. Usually, when you do that the room is empty, so you get a sense of that room as architecture when there’s no furniture in it. It’s a very different experience from when a space is lived in. I worked in theater for a while as a technical director with Ping Chong, and we were trying to create a space within a theatrical environment. Each show had a very different kind of space to it. He used a lot of films and projections and shadow plays in his work and that required a very shallow space. What I’ve experienced goes into the work, what I see goes into it.

Don Voisine, “Buzz†(2009). Oil on wood. 17 × 17 inches. Courtesy McKenzie Fine Art, New York.

La Rocco: Do you think of space as having an emotional quality?

Voisine: I use the color in my paintings to convey that, and this absolutely affects the space. My use of color is very subjective, very intuitive. It’s what sets the tone. The colors affect the interior blacks. But I usually don’t try to put in specific associations. I’m open to how people respond to the work and what they’ll see in it. I’m not trying to make something look like a landscape or something literal or literary.

La Rocco: One wants one’s work to evoke something familiar in a viewer. Do you want your painting to evoke sensation in a viewer? Or memory? Or feeling? Or should it be some kind of new experience?

Voisine: It could be all of the above. I don’t want to close off possibilities. But I don’t want to be heavy-handed about it. I don’t like it when artists say “Well, this piece is about this. This one is about that.â€

La Rocco: It’s a little like an empty stage.

Olson: One thing I learned from your work early on was that you were engaged with that history of formalist abstraction. It wasn’t a critique of it. It was a different take on it. And, to me, as a young artist, it was very inspiring because you kept that dialogue alive. You actually offered new insight into something that we had all been told was over. And I think the kind of abstraction you do lends itself to those open readings.

Voisine: Well, how I work doesn’t derive from theory. It’s all about the visual. It’s all about creating a convincing object. I’m always looking at art, and sometimes some paintings I do are a response to that. A Malevich painting might inspire me, or it could be a Titian. Or, maybe the Cézanne I saw last week in Philadelphia. It’s all a big pool to draw from.

La Rocco: Is your painting targeted at a space outside of language?

Voisine: Yeah.

La Rocco: So that in some sense attempting to discuss what it’s about is contrary to its nature?

Voisine: It’s not as if you can’t talk about it. I’m not a storyteller, you know, and that’s one of the reasons I was drawn to working abstractly in the first place. I can express the essence of something without a narrative to it.

La Rocco: Did you come to that realization slowly? Or was it something you knew from the start?

Voisine: I think I knew it early on. When I decided I wanted to paint, it was my second year of art school and from that point on, I just worked abstractly. The first abstract art that I saw I didn’t understand, I had no idea what it was coming from, but there was something about it that I felt I could connect with.

Olson: I think that this is an interesting question, in terms of narrative or storytelling. They are very abstract things. This split between abstraction and narrative happened somewhere. Where do you see your work fitting into that? Do you plan each painting out before hand? Or is it from a more subjective place?

Voisine: It’s been a long, ongoing thing. It’s hard for me to remember what the decisions were that steered me in this direction in the first place. The structures or the black forms in the paintings are kind of figured out when I start. They’re laid out on the board I’m painting on. I don’t have drawings that I blow up to scale. If I do any drawings to figure out a structure it’s a little thumbnail thing.

Olson: Is there intuition involved in the work?

Voisine: Oh, totally. I figure out the proportions as I’m making the paintings. I’ll take center points, or an edge, and build something off of either. I’ll pivot an edge, a straight edge off from a point and then build the angles off of that. Sometimes I’ll draw a cross, and then I’ll move the measure, adjusting the thickness of it, and then do another line, keeping the original point. That creates a very different angle than if I’d measured everything out.

Olson: Yeah, it’s a strange take on single-point perspective. Lets talk about the surfaces you get in your paintings.

La Rocco: When I look at those surfaces it seems there’s almost always a central area, with different types of matte, different actual colors and sheens within the black. Then that’s bordered by a different color in each painting—a very wide variety of colors in the borders from painting to painting. Then there’s this incredible attention to edges, which never seems fussy in your paintings. The edges are always careful but they’re never tight, like they’re in motion.

Voisine: Well, they’re at the service of something. I need to get those edges taut to create the spatial tension in the painting. I use tape and there are bleeds and soft edges but if they don’t distract from the line that I want or create a slackness in the space, it’s fine. A painting doesn’t really snap into place until I’ve straightened out those lines.

La Rocco: So you’re waiting on a certain experience of the painting based on the types of edges to know when the painting is starting to work, but there’s a certain margin of error.

Voisine: Right, because paintings have optimum viewing distances. When you go to a gallery or show and walk up to a painting, you find yourself going back and forth, taking a couple steps back or coming forward until you kind of settle at what is the right viewing distance. For me if it looks fine at that distance then if you see bleeds up close, it’s not an issue. But if I’m at that distance and it’s working against what I’m after, then I touch it up. But it’s not about perfection. Agnes Martin said that’s an impossible task. And was it the Chinese Buddhist painters who would always make sure there was a mistake in the work somewhere?

Olson: What types of paint do you use to get that specific black matte that occurs in your work and that sheen that you get on the gloss surfaces? I was wondering if you could go into some technical details of how you actually come up with those passages. They’re pretty flawless and elegant. At the McKenzie exhibition I noticed you can see reflections of one painting in another as you move around the gallery. That creates this extra dimension in the darkness of the central area of each painting.

Voisine: There are no secrets. There’s really nothing fancy in how I make the paintings. Everything is done in a very straight forward way. No fancy gels and mixtures. No flourishes. I use oil paint pretty much straight out of the tube. I mix the colors myself and I use Liquin to get the gloss. It takes a number of thin layers to get a smooth surface. It gets shinier with each layer. For the matte areas, I just let the paint dry as it normally does. Mars black dries pretty matte. It’s all very matter of fact. But then I try to get a painting to do as much as possible within these limitations.

Olson: In some of the recent work you have the black areas replaced by red. I was wondering if you could talk about that decision.

"Don Voisine, "Zanardi R-10" 2008, oil on styrofoam, 24 x 24 x 2 inches

La Rocco: What kind of red?

Olson: Red red.

La Rocco: I was picturing a dark red.

Olson: No, it’s red red.

Voisine: I always think about having other colors in the center and I’ve done a few using cadmium red on Styrofoam. But on the whole the use of black has provided the clarity to what I’m doing.

La Rocco: Those are your R-Value paintings. They’re all done on Styrofoam. They seemed to mark a transitional point in your work. Prior to that you were working with squares and rectangles on square surfaces like those you exhibited in the Presentational Painting exhibition at Hunter in 2006. I thought the R-Value paintings opened things up after that. And now you’re working on rectangular surfaces of varying dimensions and incorporating diagonals on a much larger scale. Weren’t the R-Value paintings titled after race car drivers?

Voisine: Yes, whatever formats I’ve used before I feel like I can use again, I can quote myself. But as far as the titles for the R-Value paintings, they were shown in a converted garage space, Abaton Garage in Jersey City. I named them after race car drivers to maintain an automotive association. Each painting also has its R-Value rating, which is based on the thickness of the Styrofoam boards I use, if its 2 inch Styrofoam it has an R-Value of 10, but if it’s 3 inch its R-Value of 15. It’s one of the few things in my paintings that is quantifiable, as a natural measure of something. Any other attributes my paintings may have are more intangible. Painting on Styrofoam boards is an ongoing and interesting side project I began in 2006 when I was invited by Mark Dagley to exhibit at Abaton Garage. It began simply as a “what would happen…?†kind of thing. As you noted Ben, the use of diagonals in the central forms was, to a large extent, developed on this surface. Shortly thereafter I began painting these more dynamic shapes on the wood panels. Each approach has generated ideas for the other. For me one of the most interesting aspects of the R-Value paintings is how people perceive them. Viewer response has been quite different from my work on wood. Although I use the same imagery on both substrates the Styrofoam paintings maintain a funkier edge, with perhaps less gravitas, and convey a quality of humor not associated with rigorous geometric forms. The contrast of such formal imagery on a basically throwaway material seems to make the paintings very approachable, even viewer-friendly.

Olson: Many of your materials are used in construction—wood panels, Styrofoam, etc. Not materials associated with formal, abstract paintings, as defined by [Clement] Greenberg or [Michael] Fried. What is your relationship to those guys? Do you read them?

Voisine: No, I don’t read them now. In the early 70s I was reading a lot of Greenberg and seeing a lot of Color Field paintings. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston was showing a lot of the painters they championed, Larry Poons, Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland. I was trying to work in that vein. Once I moved to New York I saw there was a lot more that was going on, and the narrow perspective I’d come to know from Portland Maine needed to be broadened. I wanted to make work that was more my own. I started bringing in things from the outside world, and my life. I’ve never really been a purist; it’s a sullied sort of formalism. I like my formalism a little bit dirty. [Laughter.]

Olson: In some of the paintings in your current exhibition, the central black bands break the edge of the picture plane, extending beyond. In others, they’re contained within the borders and that changes how the picture is read.

Voisine: A few years ago most of the paintings had the perimeter or border color going all the way around. But I use that less and less now. I came to understand this idea of laterality through looking at Barnett Newman. If the color is at the top and bottom only, or just on the two sides, it allows for a more expansive spatial reading. It’s not as contained. In a way, that could be an expression of me as a person, where I am.

La Rocco: There’s the issue of scale also. In this most recent show there is a whole other level of intensity and ambition, and also expression. These are some of the largest paintings you’ve done.

Voisine: Yes, but I’ve done larger work before. When I was working on canvas and linen.

La Rocco: How long ago was that?

Voisine: Um…last century! [Laughter.] I’ve made some seven and eight-foot paintings. I started working on wood in 2000 and it opened up another possibility for expression in the work. In my current show “Inauguration†is a five-foot square, that’s the biggest I’ve done on wood and it’s about as big as I can handle. You know, they just get really heavy. But I think paintings can be big without size. I don’t feel like I have to make 8-foot paintings. That’s a lot of black! Also, a big difference in the work on wood is that it reads a lot faster. It seems to have more of a graphic impact. And then if you slow down and actually look at the painting you’ll find that there’s a lot of detail, too. It gets your attention and hopefully slows you down to look. The ones on canvas were slower and they seemed to absorb light more. They were more reticent.

Olson: How long you been involved with the American Abstract Artists?

Voisine: I was nominated and accepted into the organization in 1997 and elected President in 2004. I’m usually not a joiner of groups but this seemed more important. It’s a link to history. The American Abstract Artists is an artist’s group that was founded as an exhibiting organization in 1936. From its inception the AAA played a pivotal role in the evolution of non-objective art in America. The group was born in response to the lack of professional respect accorded American Modernists in the 1930s. Among the original founding members were Ilya Bolotowsky, Balcomb and Gertrude Greene, Harry Holtzman, Ibram Lassaw and Alice Trumball Mason, just to name a few. Once the group was officially chartered and mounted its first exhibition new members included Josef Albers, Giorgio Cavallon, Carl Holty, Ray Kaiser, George L.K. Morris, and Esphyr Slobodkina. By 1940 Ad Reinhardt was writing and designing broadsides used to promote the group’s causes. During World War II many European artists came to the United States. Moholy-Nagy, Leger and Mondrian all became members during the war years. Mondrian’s work especially exerted a significant influence on the group. With the dominance of Abstract Expressionism the organization almost died out in the 50s but a revival of interest in geometric art and the new styles of the 60s such as minimalism helped revive interest. New artists joined, Brice Marden, Robert Ryman, Sol Lewitt, Dorothea Rockburne, even Robert Smithson. Many artists associated with Op art also became members, Anuskiewicz, Stanczak, Levinson, etc. This helped maintain the AAA’s vital tradition. David Reed and Merrill Wagner led the group at one time in the 80s. The AAA has always included a significant number of woman artists, in contrast to the more male dominated movements that followed.

La Rocco: Now that abstraction is a more accepted part of the artistic landscape, how do you understand the AAA’s role in contemporary culture?

Voisine: Abstraction is certainly well accepted in the art world but can still be an issue for the general public. Artists still need a forum to present and discuss ideas. Most artist groups only last a few years, while the AAA is approaching its 75th anniversary. We continue to organize member exhibitions, produce member print portfolios and catalogs, distribute published materials internationally to cultural organizations, document member history in the Archives of American Art,try to publish a journal every few years, and host critical panels and symposiums. In 2007 Kat Griefen curated an exhibition from the membership titled “Material Matterâ€, which was presented at Sideshow Gallery here in Williamsburg. The show felt fresh and current. As to the American Abstract Artist’s mission today, all I can say is, it’s not over.

La Rocco: Yeah. How do you feel about dust?

Voisine: In my painting? [Laughs.] I can’t keep it off. Did you notice stuff embedded into the surface?

La Rocco: I once watched you take out a big brush and dust a dry painting. Those dark areas will show any speck on them. I thought it might have a particular interest for you. People have done a lot of work with dust in the past—Marcel Duchamp, Gabriel Orozco and Vik Muniz.

Voisine: No, I really don’t strive to make the paintings perfect, it’s not about that at all. It’s important to me that they have a trace of the hand in them, that they are not machine made.

La Rocco: Can you tell us on the record what abstraction is? [Laughter.]

Olson: There isn’t a forty-five or a seventy-eight? [Expressive.]

Voisine: After all these years, I don’t really know. Michael Zahn makes abstract paintings that are actually representations of something. The paintings he had at the show with Linda Francis, Joan Waltemath, and myself at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery, those were box-tops, but they were abstract paintings. Those aren’t realistic but they’re abstracted from something. In a way maybe Linda’s work was the most abstract but she also works from something that is observed. My painting in that show was a tall narrow vertical, called “Debutante Twist.†For a long time I was trying to figure out how to do a vertical painting and I didn’t want it to read like a figure or doorway. But I couldn’t get past it so I just said I’ll go with it and that’s how I was able to resolve the painting. I came up with that title because the shifting of the planes reminded me of a pose in figure drawing class, a contra-posto? And the blue reminded me of tulle. My geometric figure was all dressed up. But then I don’t want people to read the title and look at that painting and say, “oh, I get it.†I’m not an advocate of anything for stylistic reasons. My work isn’t geometric because I wanted to make geometric paintings. It’s where the work led me. It’s all painting whether it’s representational or abstract. A good painting is a good painting.

La Rocco: It’s a personal decision, you come to it. It’s not an ideological position.

Voisine: No, I don’t think I’m an ideologue. I realized how uncool I was in 1991 when everybody in the art world in New York was talking about going down to D.C. to see the Sigmar Polke show. At the same time the National Gallery had a Titian show. I was like “Oh, I have to see the Titian show!†I mean the Sigmar Polke show was coming to the Brooklyn Museum within a year anyway. The Titian show was just amazing. There was a late painting he did when he was in his seventies, “The Flaying of Marsyasâ€, which was in a room all by itself. I walked in and my jaw dropped. You get up close to that painting and you find everybody in there, Bacon, Turner, Whistler. It’s basically an emotional response. And in the Boston show now there’s a late Titian painting of, I forget the saint’s name, but everything was really softly painted except a bit of the features, his right arm is held back and the division between the light and dark, the shadow on his arm, is the vein going down his bicep, which is clearly delineated. And that’s what holds everything together in the painting, just makes it work. It’s amazing, those little details that make the painting.

La Rocco: I guess that’s where I fail to understand the distinction. Abstraction. Sometimes I think I grasp it. Where I fail to understand it is that basically it’s grounded in the painting of it and in your immediate emotional response to it. It doesn’t really matter if it’s a Rothko or a Titian, and that’s where I get bogged down.

Voisine: You don’t need to get bogged down, that’s language. You just do your work.

La Rocco: Don, what do you think of Harvey Quaytman in relation to your own work?

Voisine: People ask me all the time what I think of Quaytman and I do like his work. There certainly were similarities to what I was doing before all the diagonals. People say, “It would be great to see your work together, you know, what do you think of showing with Quaytman?†It’s not as clear-cut as people think, it’s a strange relationship. We share a common visual language but when I look at his work I can’t help but think of all the different decisions I would have made. For me that’s an interesting relationship in itself.

La Rocco: What do you think the relationship of the blues is to painting?

Olson: Do you find one at all, in your own experience?

Voisine: Well, the blues is about a good woman treating you bad. And paintings can treat you bad. Paintings mess with you all the time